Manuscript of Thomas Graham’s “Bakerian Lecture” on osmotic force at the Royal Society in London in 1854

The historical basis of haemodialysis

Acute and chronic kidney failure, which can lead to death if untreated for several days or weeks, is an illness that is as old as humanity itself. In early Rome and later in the Middle Ages, treatments for uraemia included the use of hot baths, sweating therapies, bloodletting and enemas. Current procedures for the treatment of kidney failure include physical processes such as osmosis and diffusion, which are widespread in nature and assist in the transport of water and dissolved substances.

The first scientific descriptions of these procedures dates back to the 19th century and came from the Scottish chemist Thomas Graham, who became known as the “Father of Dialysis”. At first, osmosis and dialysis became popular as methods used in chemical laboratories that allowed for the separation of dissolved substances or the removal of water from solutions through semipermeable membranes.

Far ahead of his time, Graham indicated the potential uses for these procedures in medicine in his work. Today, haemodialysis describes an extracorporeal procedure, or procedure outside the body, for filtering uraemic substances from the blood of patients who have kidney disease.

Dr Georg Haas performing dialysis on a patient at the University of Giessen

The early days of dialysis

The first historical description of this type of procedure was published in 1913. John Jacob Abel, Leonard G. Rowntree and B.B. Turner “dialysed” anesthetised animals by directing their blood outside the body and through tubes of semipermeable membranes made from collodion, a material based on cellulose. It is impossible to say for sure whether Abel and his colleagues intended to use this procedure to treat kidney failure from the start.

There is no doubt, however, that dialysis treatment today continues to use major elements of Abel’s vividiffusion machine. Before the blood could be routed through the “dialyser”, its ability to clot or coagulate had to be at least temporarily inhibited. Abel and his colleagues used a substance known as hirudin, which had been identified as the anticoagulant element in the saliva of leeches in 1880.

A German doctor by the name of Georg Haas, from the town of Giessen, near Frankfurt am Main, performed the first dialysis treatments involving humans. It is believed that Haas dialysed the first patient with kidney failure at the University of Giessen in the summer of 1924, after performing preparatory experiments. By 1928, Haas had dialysed an additional six patients, none of whom survived, likely because of the critical condition of the patients and the insufficient effectiveness of the dialysis treatment. The Haas dialyser, which also used a collodion membrane, was built in a variety of models and sizes.

Haas, like Abel, also used hirudin as the anticoagulant in his first dialysis treatments. However, this substance often led to massive complications arising from allergic reactions, because it was not adequately purified and originated from a species very distant from humans. In the end, Haas used heparin in his seventh and final experiment. Heparin is the universal anticoagulant in mammals. This substance caused substantially fewer complications than hirudin – even when it was insufficiently purified – and could be produced in much larger amounts. Following the development of better purification methods in 1937, heparin was adopted as the necessary anticoagulant, and continues to be used today.

Willem Kolff

The first successful dialysis treatment

In fall 1945, Willem Kolff of the Netherlands made the breakthrough that had stubbornly eluded Haas. Kolff used a rotating drum kidney he had developed to perform a week-long dialysis treatment on a 67-year-old patient who had been admitted to hospital with acute kidney failure. The patient was subsequently discharged with normal kidney function.

This patient proved that the concept developed by Abel and Haas could be put into practice and represented the first major breakthrough in the treatment of patients with kidney disease. The success was partially due to the technical improvements in the actual equipment used for the treatment. Kolff’s rotating drum kidney used membranous tubes made from a new cellulose-based material known as cellophane that was actually used in the packaging of food.

During the treatment, the blood-filled tubes were wrapped around a wooden drum that rotated through an electrolyte solution known as “dialysate”. As the membranous tubes passed through the bath, the laws of physics caused the uraemic toxins to pass into this rinsing liquid.

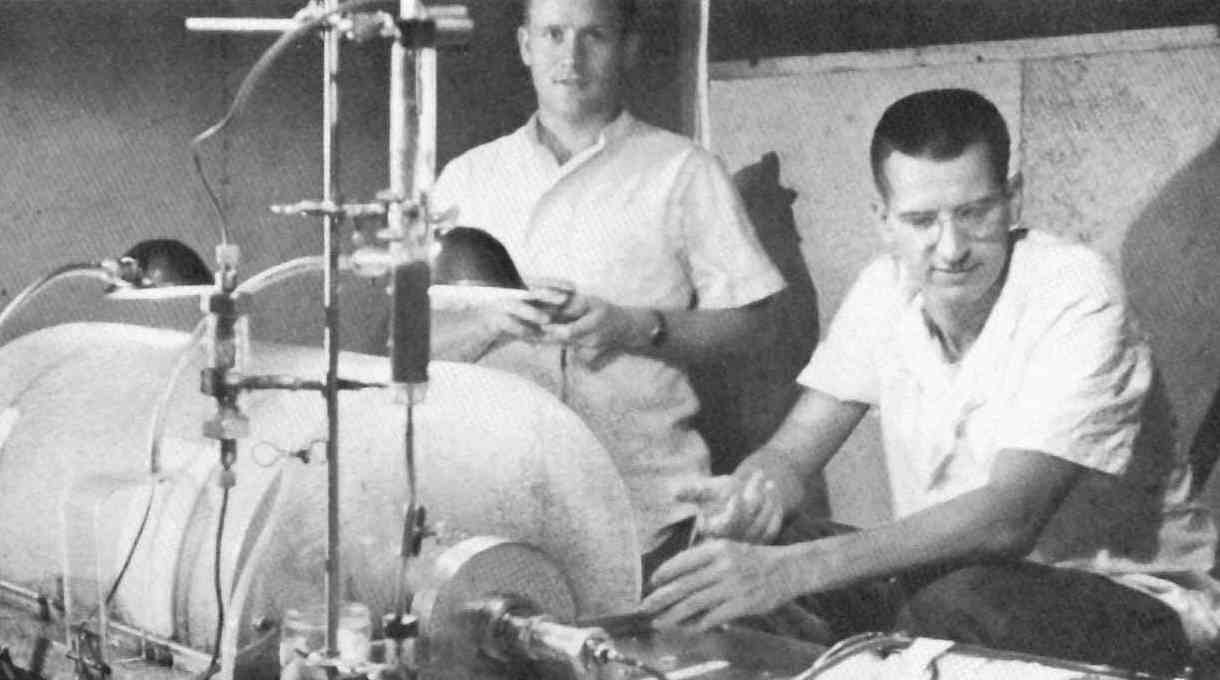

Acute dialysis during the Korean War (1952)

The rotating drum kidney

Examples of the Kolff rotating drum kidney crossed the Atlantic and arrived at the Peter Brent Brigham Hospital in Boston, where they underwent a significant technical improvement. The modified machines became known as the Kolff-Brigham artificial kidney, and between 1954 and 1962, were shipped from Boston to 22 hospitals worldwide.

The Kolff-Brigham kidney had previously passed its practical test under extreme conditions during the Korean War. Dialysis treatment succeeded in improving the average survival rate of soldiers with post-traumatic kidney failure and in doing so, won time for additional medical procedures.

Nils Alwall in 1946 with an early model of the dialysis machine

Dialysis and ultrafiltration

One of the most important functions of the natural kidney, in addition to the filtering of uraemic toxins, is the removal of excess water. When the kidneys fail, this function must be taken over by the artificial kidney, which is also known as a dialyser. The procedure by which plasma water from the patient is squeezed through the dialyser membrane using pressure is termed ultrafiltration.

In 1947, Swede Nils Alwall published a scientific work describing a modified dialyser that could perform the necessary combination of dialysis and ultrafiltration better than the original Kolff kidney. The cellophane membranes used in this dialyser could withstand higher pressure because of their positioning between two protective metal grates. All the membranes were in a tightly sealed cylinder so that different pressure ratios could be generated.

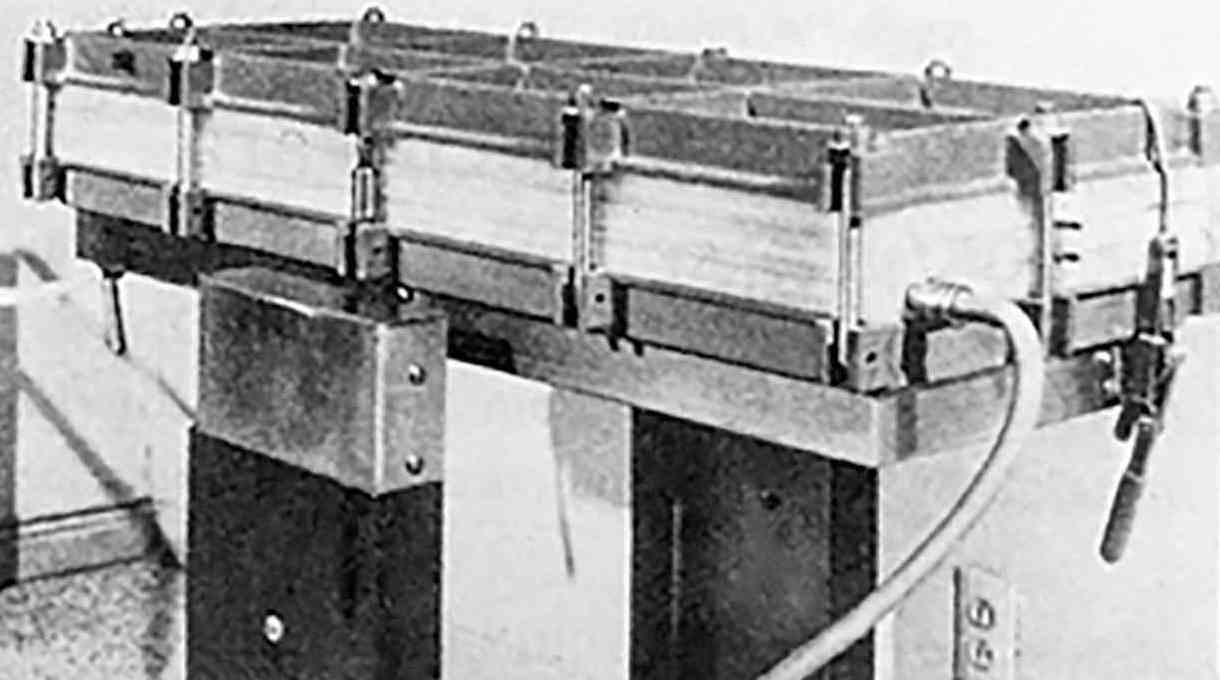

Early model of a Kiil dialyser

Further developments

By proving that uraemic patients could be successfully treated using the artificial kidney, Kolff sparked a flurry of activity around the world to develop improved and more effective dialysers. The parallel plate dialyser evolved as the most significant development of this period. Rather than pumping the blood through membranous tubes, this dialyser directed the flow of dialysis solution and blood through alternating layers of membranous material.

Just as the technology of dialysers continued to develop, so too did the scientific principles regarding the transport of substances across membranes, and these principles were applied specifically to dialysis. This work enabled scientists to develop a quantitative description of the dialysis process and allowed the development of dialysers with clearly defined characteristics.

Belding H. Scribner (1921–2003)

Vascular access and chronic dialysis

Belding Scribner made a breakthrough in this field in 1960 in the United States with the development of what would later become known as the Scribner shunt. This new method provided a relatively simple means of accessing a patient’s circulatory system that could be used over a period of several months, meaning that patients with chronic kidney disease could, for the first time, be treated with dialysis. The shunt was on a small plate that would be attached to the patient’s body; for example, on the arm. One Teflon cannula was surgically implanted in a vein and another in an artery. Outside the body, the cannulae were joined in a circulatory short circuit, hence the name “shunt.” During dialysis, the shunt would be opened and attached to the dialyser.

In 1962, further development brought the introduction of improved shunts made entirely from flexible materials. Still, the most decisive breakthrough in the field of vascular access came in 1966 from Michael Brescia and James Cimino. Their work remains fundamentally important to dialysis today. During a surgical procedure, they connected an artery in the arm with a vein. The vein was not normally exposed to high arterial blood pressure and swelled considerably. Needles could then be more easily placed in this vein, which lay beneath the skin, to allow repeated access.

This technique lowered the risk of infection and permitted dialysis treatment over a period of years. The Arteriovenous (AV) fistula remains the access of choice for dialysis patients, and some AV fistula implanted more than 30 years ago are still in use today.

Clyde Shields (1921–1971)

The first chronic haemodialysis patient

This development allowed the long-term treatment of patients with chronic kidney failure. In the spring of 1960, Scribner implanted a shunt in American Clyde Shields in Seattle. Shields became the first chronic haemodialysis patient, and the dialysis treatments allowed him to live an additional eleven years before dying of cardiac disease. These successes provided a fertile basis for the world’s first-ever chronic haemodialysis programme, which was established in Seattle in the following years.

At that time, Scribner and his team refrained from seeking patent protection for many of their inventions and innovations to ensure swift distribution of their life-saving techniques for dialysis patients. The development of improved methods for accessing blood vessels meant that patients with chronic kidney disease could be offered effective treatment for the first time.

However, in the early 1970s, a dialysis treatment lasted around twelve hours and was very expensive, due to the high outlay for materials and the treatment itself. As a result, not all kidney patients could access this life-saving therapy. In the United States, for example, committees decided on how the small number of treatment slots should be allocated – a matter of life-or-death decision making.

Modern haemodialysis

After the early successes in Seattle, haemodialysis established itself as the treatment of choice worldwide for chronic and acute kidney failure. Membranes, dialysers, and dialysis machines were continuously improved and manufactured industrially in ever-increasing numbers. A major step forward was the development of the first hollow-fibre dialyser in 1964. This technology replaced the traditional membranous tubes and flat membranes at the time with a number of capillary-sized hollow membranes.

This procedure allowed for the production of dialysers with a surface area large enough to fulfil the demands of efficient dialysis treatment. Over the years that followed, thanks to the development of appropriate industrial manufacturing technologies, it became possible to produce large numbers of disposable dialysers at a reasonable price.

They are still based on these technologies. State-of-the-art dialysis machines also monitor patients to ensure critical conditions can be detected at an early stage and treated. They feature efficient monitoring and data management systems and have become more user-friendly over recent years. A growing number of the latest generation of dialysis machines also utilise computer-controlled machines, online technologies, networking, and special software.

As the clinical use of haemodialysis became increasingly widespread, scientists were better able to investigate the unique attributes of patients with chronic kidney disease. In contrast to the early years of dialysis presented here, the lack of adequate treatment methods or technologies is no longer a challenge in the treatment of kidney patients. The present challenges stem rather from the large number of patients requiring dialysis treatment, the complications resulting from years of dialysis treatment and a population of patients that presents demographic as well as medical challenges - a population whose treatment would be unimaginable were it not for the pioneering work presented here.